Paramecium neuroscience

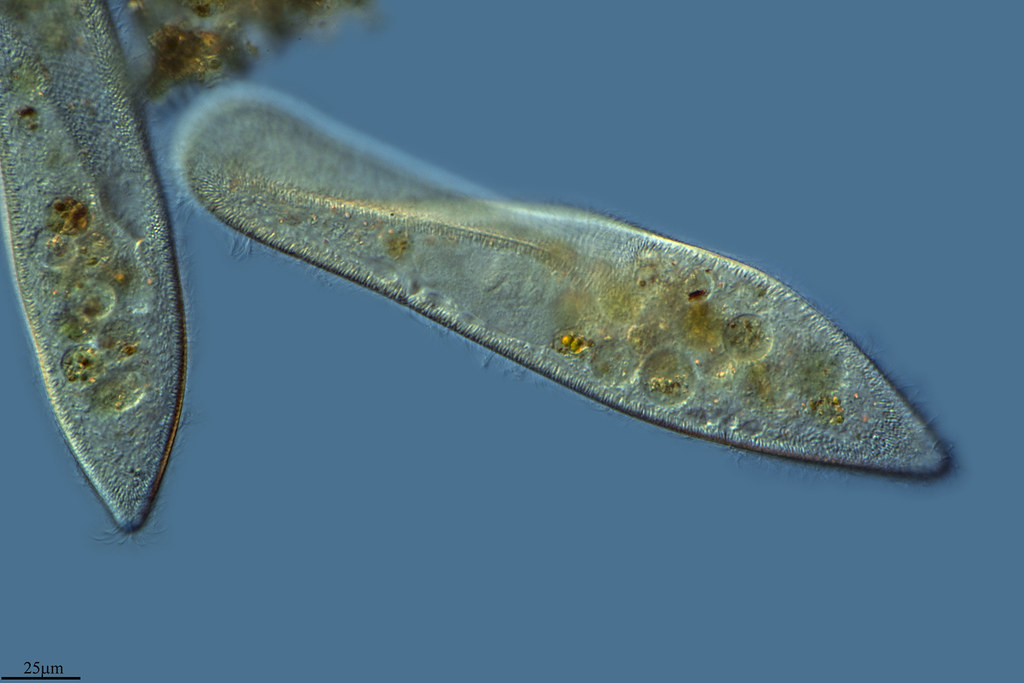

Paramecium is an excitable unicellular eukaryote that swims in fresh water by beating its cilia. This journal explores Paramecium biology from a neuroscience perspective.

Editor Romain Brette

Herbert S. Jennings

This is the second of a series of 10 papers on unicellular organisms published between 1897 and 1902. This paper describes in much detail the avoiding reaction of Paramecium, and how it is involved in behavior.

When Paramecium comes in contact with a stimulus, be it an obstacle, some chemical substance (or lack of it), cold or hot waters, it gives the avoiding reaction: it swims backward for a little while, then turns to a new direction and swims forward again. According to Jennings, this is the basis of essentially all of Paramecium’s behavior. For example, paramecia gather in a drop of acid. This does not occur by the cell turning in the direction of the chemical source, caused by the spatial gradient of concentration over the cell. Instead, paramecia wander until they swim through the drop; nothing particular happens at that point; then when they hit the border of the drop again, they give the avoiding reaction. As a result, they stay in the drop.

A large part of the paper is devoted to the detailed description of the avoiding reaction. To observe these details, he used two methods. The first one is to put the cells in gelatin: they swim slowly and cilia can be observed more easily. The second one (possibly complementary) is to add some carmine so as to visualize the water flows produced by the cilia.

Paramecium swims in spiral, revolving from right to left, with the oral side facing the axis of the spiral. The avoiding reaction is decomposed as follows. First, all cilia reverse, including the oral cilia; thus, water is expelled from the mouth. This makes Paramecium swim backward in spiral (also revolving from right to left). Then it slows down, oral cilia beat towards the mouth again (backward), and all cilia on the anterior half strike transversely toward the oral side. This makes Paramecium turn toward the aboral side (away from the mouth). Then the transverse stroke ceases and all locomotor cilia now strike backward, driving the cell forward. The avoiding reaction varies only in the intensity of the different components. For a very weak stimulus, cilia reverse very briefly and then Paramecium turns by a small amount. For a strong stimulus, Paramecium swims backward over many times its length, then makes a sharp turn, possibly turning more than 180°.

Thus, the new direction depends on the initial position of the oral groove. But since the organism constantly revolves along its long axis, this new direction can be described as “pseudo-random”. The new direction is unrelated to the spatial character of the stimulus. In particular, it may bring the cell back into the stimulus. In addition, if Paramecium swims backward and comes in contact with something that would normally be a stimulus (e.g. an obstacle), then it does not react. In summary, the way Paramecium behaves and navigates is not by directing itself towards certain stimuli, but rather by trial and error.

Jennings then examines again thermotaxis, which was previously observed by Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn believed that Paramecium could sense very tiny temperature gradients, but Jennings shows that it works differently. He puts paramecia on a glass slide, with one end on ice and the other heated at 40°C. Those on the hot side are very agitated and appear to change direction randomly. Those on the frozen side swim very slowly, also without apparent direction. Yet soon enough, paramecia gather on the part with moderate temperature. This occurs because they give the avoiding reaction when encountering the border between the middle part and either end, but only when coming from the middle part.

Paramecium appears to have no knowledge (no “representation”) of space. Yet, it can exhibit seemingly goal-directed behavior by the interaction between a single type of action and the environment. This is a simple illustration of the concepts of embodiment and situatedness (body and environment are integral parts of the behaving system).