Paramecium neuroscience

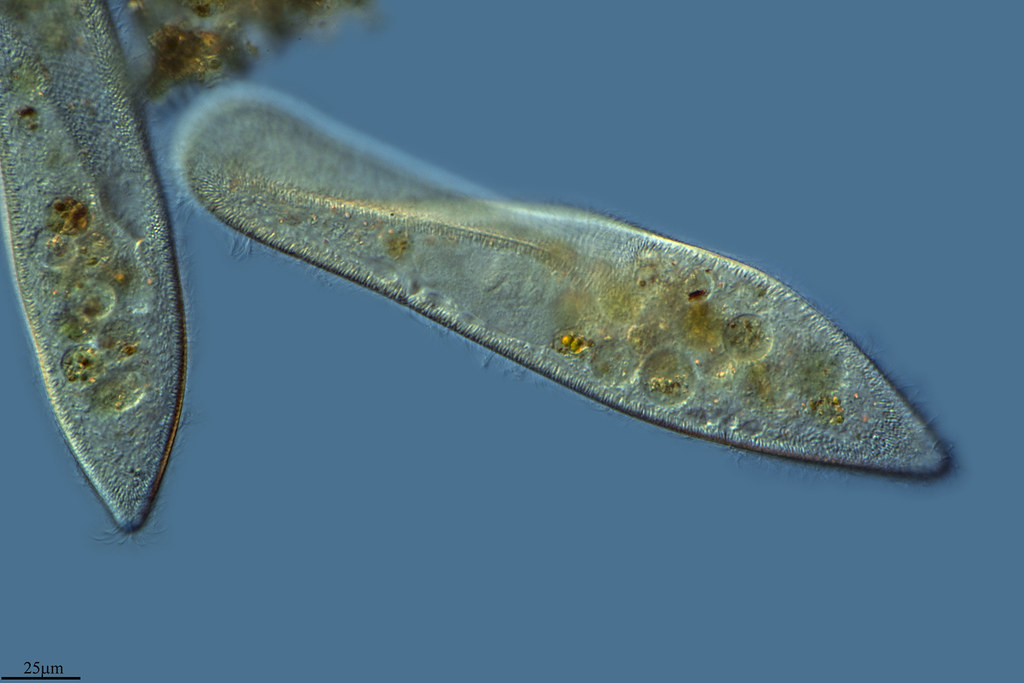

Paramecium is an excitable unicellular eukaryote that swims in fresh water by beating its cilia. This journal explores Paramecium biology from a neuroscience perspective.

Editor Romain Brette

Discrimination Learning in Paramecia (P. caudatum) (2006)

Harvard L. Armus, Amber R. Montgomery, Jenny L. Jellison

DOI: 10.1007/bf03396029

In the 20th century, there have been many attempts to demonstrate learning in Paramecium, but they have been controversial. In a 1979 review, here is how Applewhite introduced the subject: “I like protozoa, but they do not like me”, and it is worth quoting his conclusion in full:

“Learning (beyond habituation) has not been adequately demonstrated in protozoa. Claims of learning have either not been confirmed in replications, or controls are lacking to rule out alternative explanations to learning. In spite of this, I find no a priori reason why protozoa cannot learn. Most of the protozoan experiments reported on here are relatively simple to perform and I would encourage their replication by others. As for me, I give up.” (PB Applewhite (1979), Learning in Protozoa, Biochemistry and physiology of protozoa).

This paper reports a more recent try. Unfortunately, in my view it is not successful. Nevertheless, it does report some non-trivial results. The idea of the study is to train paramecia to go a lighted region using electrical shocks. To understand the results, it is crucial to understand both photosensitivity and the response to electrical stimulation.

First, several reports have shown that paramecia are photophobic, i.e., they tend to avoid bright light and gather in the dark. They do this as usual by the avoiding reaction triggered by light (as well as speed increase). This behavior adapts over time, with a time scale of seconds (I will comment on specific papers later). I believe this is genuine because it has been reported by several authors, on several species. However, some authors claimed to have failed observing it. It might be that it depends on culture conditions (e.g. whether there is a dark-light cycle). This might make it a good candidate for a conditioned stimulus.

Second, the response to electrical shocks is well known, and has been described by Ludloff in 1895 (see my comment). When an electrical field greater than 500 V/m is applied, paramecia turn to face the cathode and then swim forward. This happens because the front part of the membrane is depolarized while the rear part is hyperpolarized, and so the front cilia reverse while the rear cilia speed up. The authors of this paper present these responses in a somewhat peculiar way. They stimulate paramecia in the cathodal half of the apparatus, and describe this as “positive reinforcement”, because paramecia then move towards the cathode. Conversely, stimulation in the anodal half (described in another paper published the same year, Armus et al. 2006) is considered as an aversive stimulus. However, it is exactly the same physical stimulus in both cases, so describing it as either positive or negative reinforcement depending on the cell’s location when it is applied is a little odd.

In any case, what they find in this paper is that if the bath is divided in two halves, with one half lighted and the other dark, and paramecia are electrically stimulated when they are in the cathodal half, then after this “training” they spend more time in that half (compared to a control), even though there are no more electrical shocks. In addition, if light and dark regions are switched after training, then paramecia also switch their preferred region. Finally, random pairing has not effect. This seems quite promising: it seems that paramecia learn to go to the region whose light intensity was associated with electrical stimulation. However, the other paper published by the same group on the same year (Armus et al. 2006) challenges this interpretation. In that study, they stimulated paramecia in the anodal half, and then found this time that the cells spend less time in that half after training. The authors describe the “anodal stimulation” as aversive (because cells move away from the anode) and the “cathodal stimulation” as attractive, but from the cell’s viewpoint, this is exactly the same electrical stimulus. In one case, pairing light and electricity yields a phototactic behavior, but in the other case it yields a photophobic behavior. Something is going on!

In addition, a later publication from the group showed that even a pause of 1 minute (the minimum tested) with uniform lighting between training and testing erased the “memory” (Mingee 2013). Importantly, the uniform lighting was dark if the cathode was lighted. Alipour et al. (2018) successfully replicated the experiment, but noted that the phenomenon was only seen when the cathode was lighted, not when it was dark.

My interpretation is the following. When paramecia are stimulated in the lighted cathodal half, they move towards the cathode and therefore they spend more time in the cathodal half during training. This is indeed seen in the experimental results, from the first session. As a result, the photophobic response adapts. This makes them spend more time in the lighted half after “training” than controls. Crucially, it does not make them phototactic, it simply makes them less photophobic. Indeed, in the experimental results it can be seen that control cells spend more time in the dark half, and “trained” cells spend about the same amount of time in both halves. According to this interpretation, the same phenomenon should be seen if paramecia were simply exposed to uniform light before testing (which has not been tested).

Thus, unfortunately this set of studies did not convincingly demonstrate learning in Paramecium.