Paramecium neuroscience

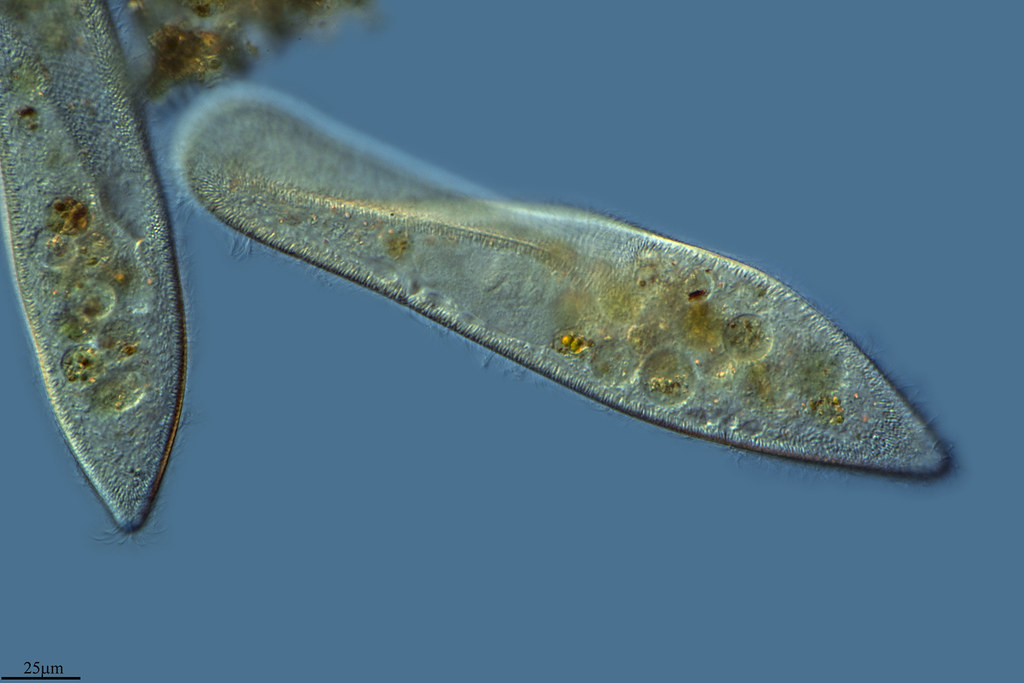

Paramecium is an excitable unicellular eukaryote that swims in fresh water by beating its cilia. This journal explores Paramecium biology from a neuroscience perspective.

Editor Romain Brette

Attempts to retreat from a dead-ended long capillary by backward swimming in Paramecium (2014)

Itsuki Kunita, Shigeru Kuroda, Kaito Ohki, Toshiyuki Nakagaki

PubMed: 24966852 DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00270

This paper reports an interesting behavior, where Paramecium escapes from a narrow capillary by swimming backward for a long time. A single paramecium (species is not given, but I presume from the size that it is P. caudatum) is placed in a thin capillary (80 µm inner diameter), so thin that the cell cannot turn. The capillary is closed by oil at both ends. The cell swims forward to one end, then gives the avoiding reaction, swims backward for about 400 µm, then swims forward again and repeats. After about 1 min, corresponding to 40 avoiding reactions, the backward distance starts increasing and after 1 more min (roughly 5 avoiding reactions) it is 3 mm (about 10 times longer) and it then remains stable. It is as if the organism realizes it is trapped and tries to exit by potentiating the avoiding reaction.

What is the physiological basis of this phenomenon? Given that cilia orientation is controlled by intracellular calcium, the results seem to imply that after a number of avoiding reactions, more calcium enters the cilia during an avoiding reaction. This could be because the calcium current gets potentiated, or because inactivation is reduced, or because the action potential lasts longer (e.g. through an inhibition of the K+ currents). Some electrophysiology would be helpful.

The authors propose a Hodgkin-Huxley type model, based on the hypothesis that a slowly inactivating voltage-gated calcium current gets potentiated after each stimulus. How this potentiation occurs is not modelled. The model is problematic because it models the calcium current as voltage-inactivating, whereas it is inactivated mainly by intracellular calcium. The link between ciliary reversal and calcium is also incorrectly modelled: it is stated that the cilia reverse as long as the calcium current flows, but in reality they reverse as long as there is (sufficient) calcium in the cilia, and therefore ciliary reversal can last much longer than the action potential. One would need to model calcium dynamics. Nonetheless, it remains that a modulation of the calcium current kinetics (or amplitude) by repeated stimulation is a plausible hypothesis. It could be linked to calcium-dependent facilitation, a known property of L-type calcium channels.