Paramecium neuroscience

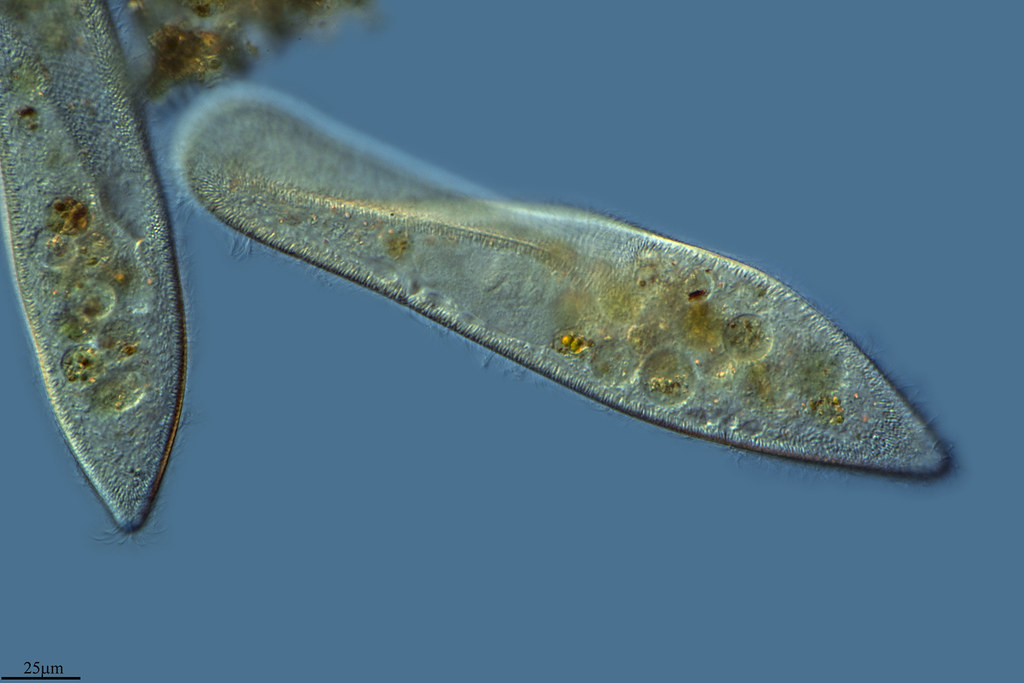

Paramecium is an excitable unicellular eukaryote that swims in fresh water by beating its cilia. This journal explores Paramecium biology from a neuroscience perspective.

Editor Romain Brette

When put at the bottom of a tube, Paramecium quickly swim up to the top, a phenomenon called (negative) gravitaxis. There have been many studies of Paramecium gravitaxis, but this one is the first thorough study on the subject. Jensen also discusses gravitaxis in other microorganisms, but I will only discuss Paramecium. Note that as I am not a German speaker, this review is based on an automatic translation.

Paramecia accumulate at the top of a 20 cm tube in about 5 minutes. First, Jensen asks whether this is genuinely gravitaxis, and not attraction by some other stimulus. He shows for example that it is not due to the presence of oxygen at the interface with air, as it occurs also when the tube is closed. However, the phenomenon appears to be perturbed by chemotaxis. In particular, if there are many paramecia, then after some time they leave the water surface and the meniscus and swim a little bit deeper. He speculates that this is due to a higher concentration of salts at the surface because of evaporation. Jennings (1897) showed later that in fact it occurs because paramecia are attracted to CO2, which they themselves produce by breathing, and CO2 escapes at the interface with air, therefore they concentrate a little bit below.

He then shows that if the surface is warmer than the rest, then gravitaxis is not observed. Thus, the phenomenon can be easily suppressed by other stimulation. Nevertheless, gravitaxis still remains when other stimulation sources are removed. It can also be reproduced artificially by centrifugation: paramecia accumulate at the central end.

The second question Jensen wants to address is whether gravitaxis might be due to a passive orientation of the cell. For example, if the posterior side were heavier than the anterior side, then the cell would turn so as to orient itself upward. However, he shows with dead cells that this is not the case: they sediment to the bottom with no particular orientation. He speculates that the organism must be sensitive to pressure differences. Specifically, his hypothesis is that cilia are excited by local pressure, and so the cilia below would beat more strongly than those above. This would make the cell turn upward.

Interestingly, the question of the mechanism is not fully resolved and Jensen’s hypothesis sums up the different views on the debate. Machemer has been arguing in a series of papers that Paramecium can sense pressure differences between the anterior and posterior ends, as it is known that those are differentially sensitive to mechanical stimulation (see e.g. Machemer (1996), A theory of gravikinesis in Paramecium). This would result in hyperpolarization when Paramecium is oriented upward, making the organism speed up, and depolarization when it is oriented downward, triggering an avoiding reaction (change in swimming direction). However, Roberts (2010) has shown that gravitaxis is mostly explained by the fact that trajectories are curved upwards, which he attributes to a mechanical interaction between cilia beating and the sedimentary flow. This is somewhat similar to Jensen’s 1893 hypothesis, except it does not require sensory sensitivity, only mechanical interaction.