Paramecium neuroscience

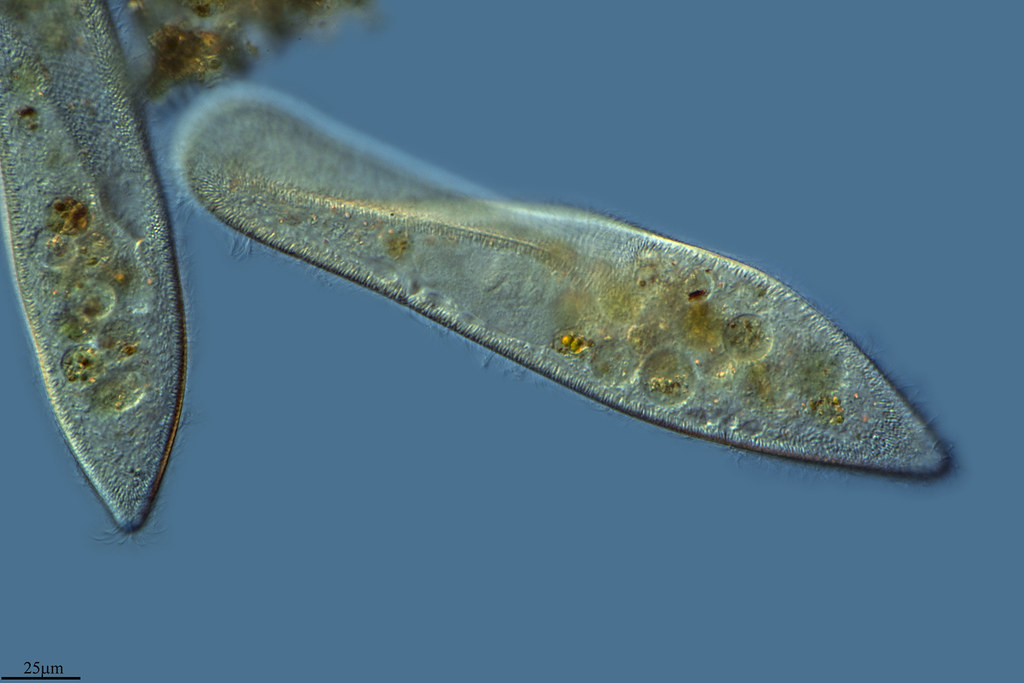

Paramecium is an excitable unicellular eukaryote that swims in fresh water by beating its cilia. This journal explores Paramecium biology from a neuroscience perspective.

Editor Romain Brette

Herbert S. Jennings

PubMed: 16992389 DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.1897.sp000656

I believe this is the first paper by Jennings on Paramecium. Jennings is best known for his wonderful 1906 book, Behavior of the lower organisms, but he has written many detailed papers on the behavior of Paramecium and other unicellular organisms (see this collection of papers).

Jennings describes a number of experiments, which are generally quite simple. Here is how he describes the culture method: “The Paramecia used in the experiments were procured in the customary manner. A handful of hay or grass is placed in a jar and covered with hydrant water. In a few weeks the solution of decaying vegetable matter swarms with Paramecia. In such a jar they may be kept for indefinite periods in almost unlimited numbers.”. He then washes paramecia by gravitaxis (dilutes the cells in a tube, picks them at the top).

The paper covers two aspects of behavior: chemotaxis and thigmotaxis. He studies chemotaxis by putting paramecia between two coverslips and inserting drops of various substances in the middle. He finds that acids are attractive at low concentration, repellent at high concentration; alkalies are repellent; some salts repellent, as well as some organic compounds. He demonstrates that the chemotactic power of various solutions is unrelated to their osmotic properties, i.e., the phenomenon is not “tonotaxis”. An observation that he finds puzzling is that the culture medium to which paramecia are accustomed is repellent, because it is alkaline. For example, if a drop of distilled water is inserted, they gather into it.

To Jennings, the most relevant aspect of Paramecium chemotaxis is their attraction to CO2. He shows that paramecia produce CO2 and are attracted to it at low concentrations (at higher concentrations they are repelled). This is the basis of collective behavior that he observes, with paramecia gathering together in various circumstances. For example, when put at the bottom of a watch glass (I’m assuming, at high enough density), they gather at the bottom. He explains this by the fact that CO2 escapes to the air near the surface, so regions close to the surface have lower CO2 concentrations. This explains Jensen’s findings on gravitaxis.

The second aspect that he studies is thigmotaxis or “contact reaction”, the fact that paramecia attach to decaying plants, but also paper, linen, fibers (not to clean glass or wood). This seems to be due to the texture of the object, and not to chemotaxis. In fact, the gathering of paramecia on such objects is due to the combination of the contact reaction and chemotaxis: a Paramecium touches by chance some object and attaches to it, then others sense the CO2 and soon enough there is large gathering.

Jennings then introduces carmine in the water so as to visualize water flows produced by the cilia. He finds that when Paramecium is attached, the cilia against the surface are still and other locomotor cilia are quiet or quiver, while oral cilia beat backwards toward the mouth - in other words, Paramecium is feeding. Finally, he shows that when an electrical current is applied, Paramecium remains attached. For example, if it has its anterior end attached with the cathode on the posterior side, then the electrical field makes posterior cilia reverse, but this occurs only transiently and repeats at variable intervals. This is a bit intriguing in terms of electrophysiology (which of course Jennings did not know about). Perhaps the ciliary calcium channels open, then the membrane repolarizes through a calcium-dependent K+ channel (which is known to exist). What is intriguing is that the same phenomenon does not seem to occur when the cell is not attached. To my knowledge, the contact reaction has not been studied electrophysiologically.